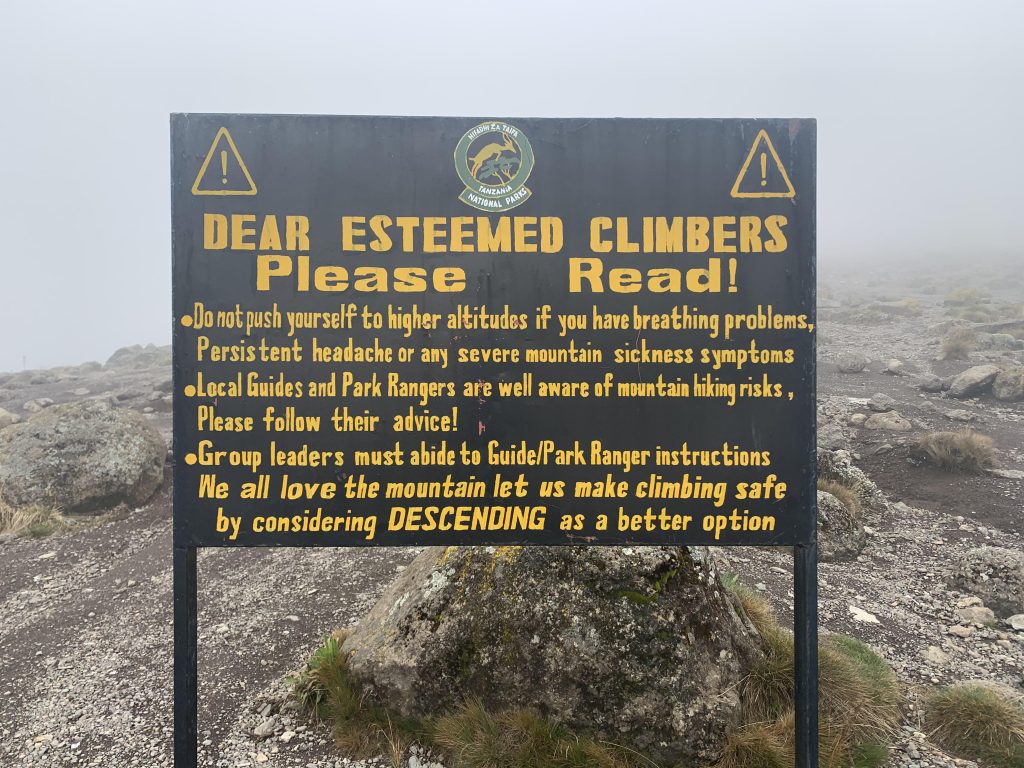

Altitude sickness on Kilimanjaro is one of the biggest challenges climbers face. Climbing Mount Kilimanjaro is a life-changing adventure, but it’s important to remember that you’ll be pushing your body far beyond its comfort zone. One of the greatest challenges isn’t the distance or even the cold — it’s the altitude. Safety guidelines for high altitudes.

At 19,341 ft (5,895 m), the summit of Kilimanjaro lies in what doctors call the “extreme altitude zone”. Up here, there’s only about half the oxygen available at sea level. For some people, the body struggles to adapt to this sudden drop in oxygen, leading to a condition called Acute Mountain Sickness (AMS).

Why Altitude Affects Us?

Many people assume altitude sickness happens because there’s “less oxygen” in the air. Technically, the percentage of oxygen in the atmosphere doesn’t change; it stays at about 21% whether you’re on the beach or high in the mountains. The difference is air pressure.

As you climb higher, air pressure decreases, and with it the number of oxygen molecules in each breath. At 12,000 ft (3,600 m), for example, every breath delivers around 40% fewer oxygen molecules compared to sea level. Your body has to work much harder to supply the brain and muscles with the oxygen they need.

Acclimatization comes in a gradual process where your body adapts to thinner air by:

- Breathing deeper and faster

- Producing more red blood cells to carry oxygen

- Improving circulation in areas of the lungs usually underutilized

- Releasing oxygen from hemoglobin more efficiently

If your body can’t keep up, that’s when altitude sickness on Kilimanjaro symptoms appears. Understanding altitude sickness on Kilimanjaro early can help you take precautions and climb safely.

Who Is at Risk?

Here’s the tricky part: anyone can get AMS. It doesn’t matter how fit you are, your age, or how much you’ve trained. Genetics plays a big role, and susceptibility varies from person to person.

That said, you may be more at risk if you:

- Live at sea level and are unaccustomed to altitude

- Climb too high, too quickly

- Push yourself physically without proper rest

- Have anemia, heart, or lung conditions

- Use certain medications that suppress breathing (like strong sleeping pills or sedatives)

- Have had AMS before

On Kilimanjaro, over 75% of climbers will feel at least mild altitude sickness on Kilimanjaro symptoms at some point above 10,000 ft (3,000 m). Understanding altitude sickness on Kilimanjaro is key to recognizing it early and taking action before it becomes serious.

Recognizing the Symptoms

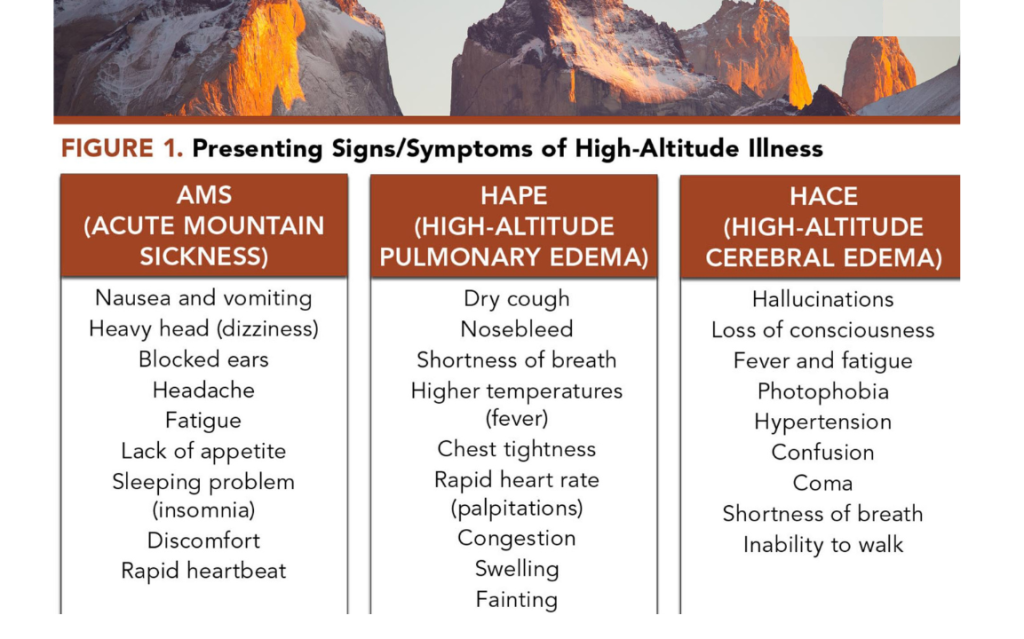

AMS comes in three levels of severity:

Mild AMS (very common)

- Headache

- Nausea or dizziness

- Loss of appetite

- Shortness of breath on exertion

- Fatigue

- Trouble sleeping

This stage is unpleasant but usually manageable. With rest and time, your body often adjusts within a day or two.

Moderate AMS (more serious)

- Severe, throbbing headache (unrelieved by medication)

- Vomiting

- Increasing fatigue and weakness

- Difficulty with coordination (ataxia)

- Shortness of breath even during light activity

At this point, continuing higher is dangerous. A descent of even 1,000 ft (300 m) usually improves symptoms, and within 24 hours at a lower altitude, most climbers feel much better.

Severe AMS (life-threatening).

- Shortness of breath at rest

- Loss of ability to walk or think clearly

- Confusion or irrational behavior

- Fluid build-up in lungs (HAPE) or swelling in the brain (HACE)

These conditions can develop rapidly and are fatal if ignored. Immediate descent of at least 2,000 ft (600 m) is essential, often combined with bottled oxygen and urgent medical care. Hiking technique

HAPE and HACE – The Serious Complications.

High Altitude Pulmonary Edema (HAPE).

This happens when fluid leaks into the lungs, preventing effective oxygen exchange.

Symptoms:

- Tight chest and shortness of breath, even while resting

- Cough producing frothy or watery fluid

- Extreme fatigue

- A sense of suffocation at night

- Confusion or irrational behavior

High Altitude Cerebral Edema (HACE).

This occurs when fluid builds up in the brain, restricting blood and oxygen flow.

Symptoms:

- Severe headache

- Loss of coordination

- Disorientation, confusion, or memory loss

- Hallucinations

- Eventually, unconsciousness or coma

How Mateys Wild Tours Keeps You Safe.

At Mateys Wild Tours, safety comes first. Our guides are trained in high-altitude medicine and perform daily health checks for every climber. We monitor oxygen saturation levels, heart rate, and symptoms carefully throughout the trek. See this Video

Here’s what we do:

- Encourage a slow, steady pace to maximize acclimatization

- Choose itineraries with extra acclimatization days

- Carry bottled oxygen and portable stretchers on every climb

- Provide immediate descent support if symptoms worsen

Mild AMS is expected on Kilimanjaro, but serious complications are rare when climbs are managed properly and symptoms are never ignored.

The Best Protection: Go Slow & Listen to Your Body.

The single biggest cause of AMS is going too high, too fast. That’s why we always recommend choosing a longer itinerary (7–9 days rather than rushing in 5–6).

Walking “pole pole” (slowly, slowly, in Swahili) isn’t just advice, it’s a strategy that saves lives. Taking your time gives your body the chance to adapt and greatly improves your chances of standing proudly on the summit.

Concluding Remark

Kilimanjaro is an incredible mountain, but it’s also a test of patience, endurance, and respect for nature. AMS reminds us that altitude is the true challenge, not just the trail.

At Mateys Wild Tours, our goal is to get you to Uhuru Peak safely, but just as importantly, to get you back down healthy and strong. Understanding altitude sickness on Kilimanjaro and having the right preparation and a good team will make your summit journey as safe as it is unforgettable.

![How Did Mount Kilimanjaro Get Its Name? Meaning & History Explained [2025 Guide]](https://www.mateyswildtours.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/06/How-Did-Mount-Kilimanjaro-Get-Its-Name-Meaning-History-Explained-2025-Guide-150x150.jpeg)